The revolutionary technology of "Jurassic Park" was so groundbreaking at the time that its impact is difficult to imagine for those who weren't around when the film was first released. Audiences today are used to giant spectacles brought to life through mostly CGI, but "Jurassic Park" represented a huge step in visual effects for cinema, fully realizing the possibility of bringing dinosaurs to life on the big screen. It was Stan Winston, one of the most important and influential special effects artists in the history of film, who helped to turn "Jurassic Park" into reality.

Steven Spielberg conceived of a film adaptation of Michael Crichton's novel before it was even published, and he was determined to use full-sized animatronic dinosaurs. This would be an ambitious undertaking, a project that would need to convincingly bring to life extinct creatures that only existed in museums, books, and the imagination of children. The filmmaker consulted Bob Gurr, a ride designer for Disney parks who also designed the giant animatronic for the King Kong Encounter attraction at Universal Studios Hollywood. But designing a moving, artificially breathing monster for a film set is a lot different than running a theme park animatronic, whose movements don't have to be as versatile. Spielberg knew that visual effects pioneer Stan Winston and his team of artists and engineers might have been the only people capable of taking on the daunting task.

Bingo! Dino DNA

By the time "Jurassic Park" was in the works, Winston already had an accomplished career as a makeup and visual effects artist for technically outstanding works like the "Terminator" films, "Aliens," the "Predator" films, and "Edward Scissorhands." Nevertheless, he had never done anything quite like "Jurassic Park." In order to bring the film's diverse cast of dinosaurs to life, Winston and his team needed to incorporate a multitude of techniques that combined hands-on modeling with complex mechanics.

Winston's crew designed the dinosaurs on paper first to give Spielberg a feel for what the creatures would like, with concept artist Mark "Crash" McCreary handling the final rendering (via American Cinematographer magazine). Then the crew turned the drawings into sculptures that were one-fifth of their life-sized counterparts (the brachiosaurus was one-nineteenth of its size due to its massive scale). These served as models for both the full-size animatronics as well as the computer-generated effects from Industrial Light & Magic (ILM).

Skeletons And Clay

Now came the crux of the assignment for Winston's team: turning these models into moving, life-sized dinosaurs. The artists built wooden frames to serve as the bare skeleton, then molded fiberglass and clay on top. Yet another skeleton, this one made of metal, consisted of a complex system of mechanical features, turning the model into a bona fide animatronic. Finally, the crew covered the whole thing in a skin. Winston explains the process in his own words in an article published in the American Cinematographer magazine:

"We covered the wooden patterns with fiberglass to create a smooth solid surface, then started putting clay on it to make our finished sculpture, and that became our sculpting armature. It ended up looking exactly like a very large version of those wooden dinosaur skeleton toys you can buy! The form of the dinosaur was done virtually by mechanical drawing, so our full-scale creations were identical to our 1/5th-scale maquettes. All we had to do then was to sculpt the skin and the detail. Later, I learned this was exactly the way the Statue of Liberty was built!"

Living And Breathing Dinosaurs

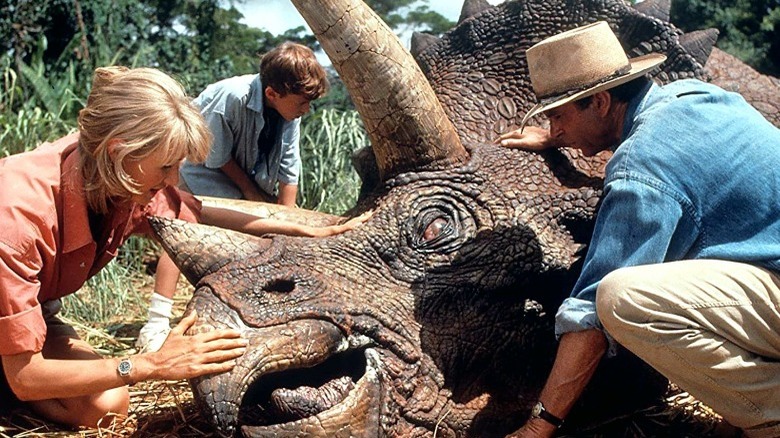

Winston worked with a design team headed by mechanical effects supervisor Michael Lantieri to bring the dinosaur models to life through movement. A mixture of mechanical controls, rigs and dollies, and good-old-fashioned physical pushing and pulling maneuvered the dinosaurs on camera. Some dinosaur species required specific creative touches, like the nimble velociraptors or the gigantic T-Rex, the latter being the largest creation Winston ever built. Meanwhile, the raptor sequences utilized both puppets and actors in suits, a more traditional monster movie technique, to make their movements feel more eerily life-like. For the T-Rex, Winston's team installed a counterbalance in the dinosaur's head that could absorb the shock of a sudden stop. This would make for more organic movements so the centerpiece creature of "Jurassic Park" wouldn't look jerky and robotic.

The process to create living dinosaurs on film was a multifaceted marathon. Its contestants were illustrators, sculptors, puppeteers, and mechanical engineers, not to mention the computer effects artists at ILM. Stan Winston and his team of artists took two years to work on "Jurassic Park," but their ambitious efforts paid off and their legacy lives to this day in every bit of special effects movie magic.

Read this next: The 15 Worst Sci-Fi Movies Of The 21st Century (So Far)

The post Steven Spielberg Only Trusted One Man to Bring Jurassic Park to Life appeared first on /Film.