Margery Williams was born in London on July 22, 1881, and died September 4, 1944, in New York City. Though she published twenty-seven books, including five translations of works from French and Norwegian, and though she won the John Newbery Honor Medal for her novel Winterbound (1936) in 1937, she is primarily known today as the author of The Velveteen Rabbit.

While biographers make no mention of her mother that I have been able to find, it is frequently noted that Williams’s father, Robert Williams, was a warm and encouraging influence. A fellow of the classics at Oxford as well as a barrister and an opinion writer for periodicals, he held liberal views of education, prescient of today’s unschooling movement.

Williams was taught to read early and then allowed to explore her interests freely, without instruction and largely alone because her only sister was six years older. Anne Carroll Moore, who knew Williams well, quotes her as saying, “My favorite book in my father’s library was Wood’s Natural History in three big green volumes, and I knew every reptile, bird and beast in those volumes before I knew the multiplication table.” Her father’s death, when Williams was seven years old, was a deeply saddening formative experience that would shape her artistic vision.

A century later, readers may not be aware of this postwar context for young readers who had suffered deprivation and loss.Williams spent the rest of her childhood back and forth between the United States and England. After two happy years at the Convent School in rural Pennsylvania, ending at age seventeen, she knew she wanted to become an author. At nineteen, she returned to London hoping to publish. That she did and more. Peggy Whalen-Levitt sums up Williams’s next few years: “By 1906, when she was twenty-five, she had published four adult novels; married Francesco Bianco, a dealer in rare books; and given birth to two children.”

Williams’s attentions turned away from writing to care for Cecco (born August 15, 1905) and Pamela (born December 31, 1906). They lived in Paris and then Turin while Captain Bianco served in the Italian Army during World War I and returned to London before the family permanently relocated to the United States.

They moved in 1921 to support the artistic development of Pamela, a child prodigy in drawing and painting. After the twelve-year-old’s 1919 solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London, Gertrude Vanderbilt took Pamela under her patronage and arranged an exhibition at the Anderson Galleries in New York. Upon viewing Pamela’s artistic works, which were inspired by the works of Walter de la Mare—a well-known poet whose writing for children Williams greatly admired, de la Mare himself was inspired to write an ekphrastic collection of poems.

Heinemann published their recursive collaboration in a 1919 volume, Flora: A Book of Drawings with Illustrative Poems. According to the prefatory note about Pamela Bianco, “Her remarkable talent for decorative invention, and her poetic imagery drew crowds to the exhibition, and obtained the enthusiastic praise of the entire press” (Bianco and de la Mare). Today, it may surprise most children’s literature scholars to learn that, during their lifetimes, Pamela Bianco was actually far more famous than her mother.

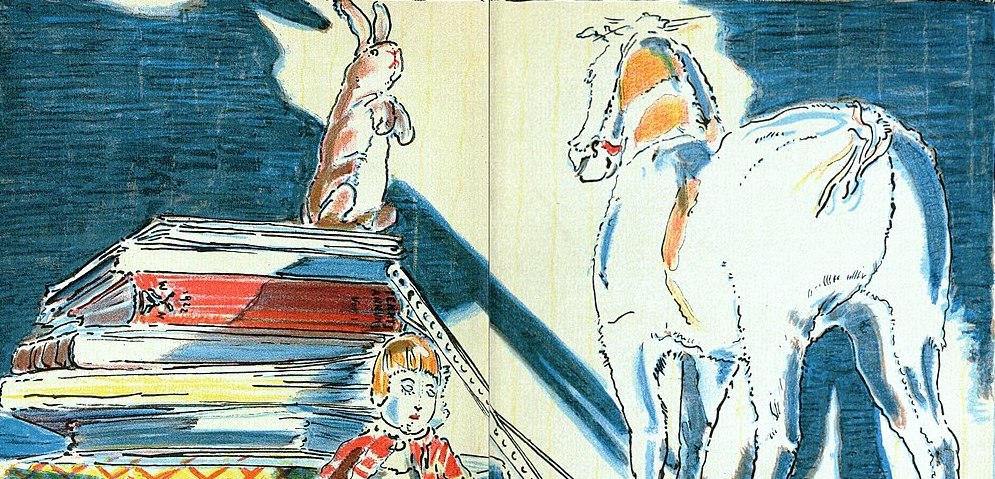

Inspired by de la Mare, with her children now in adolescence, Williams resumed writing, turning her hand to “stories she had told them [her children] when they were small, stories about their toys” as well as “those she herself had loved as a child.” The first of these was based on her “almost forgotten Tubby who was the rabbit, and old Dobbin the Skin Horse” and published by Harper’s Bazaar in 1921 “as a vehicle for original illustrations by Pamela.” We now know this story, “The Velveteen Rabbit,” as her first children’s book.

In it, Harry E. Eiss writes, Williams “discovered the wonder and sense of the miraculous invoked by the works of de la Mare and expressed it through a simplicity and directness matching a child’s worldview.” Moore first encountered The Velveteen Rabbit when its American publisher, George H. Doran Co., sent her the prepublication pages and asked her opinion on how the book would sell. She found the themes stunningly poignant because she had recently spent time in France and England where she had formed “vivid first-hand impressions of children whose toys and pets and books had been destroyed.” A century later, readers may not be aware of this postwar context for young readers who had suffered deprivation and loss.

While the magical ending isn’t realism, it’s realistic in its aims.A number of successful children’s books followed The Velveteen Rabbit in rapid succession, now under the name Margery Williams Bianco. Two were illustrated by Pamela Bianco, including The Little Wooden Doll (1925) and The Skin Horse (1927), the latter a subject of brief discussion by Scott T. Pollard and Kara K. Keeling in this volume.

In “A Tribute to Margery Bianco,” Williams’s contemporary and friend of the family Louise Seaman Bechtel describes the reason for the author’s success: “This kind of imagination, playing not upon fairies but upon the real things a child knows, his toys and his pets, struck a note… to which children will always answer.” She singles out Williams’s “touch of the true artist that keeps the most important thing predominant in a dramatic simplification. The Velveteen Rabbit belongs to a Boy—we do not know his name, or what his home looked like, or exactly how many people were in his family, because it doesn’t matter to the rabbit’s story.”

Williams shared her philosophy of “Writing Books for Boys and Girls” in a speech to the National Council of Teachers of English in 1936, the year her Newbery Honor Book Winterbound was published. “In writing a real life story I think it should be real life, as far as one can present it,” she said. “Things shouldn’t be made any easier than they actually are” because it’s unfair to readers when “each difficulty is promptly surmounted and something always turns up in time to save a situation.”

She believed: “Children know much better. They know that things don’t happen just that way, and that if you really want to accomplish anything at all—no matter how small—you generally have to work pretty darn hard over it, and go through a lot of misgivings and discouragement along the way.”

This philosophy, from someone who drew on her own and her children’s real-life toy stories and who had also lost her father at an early age, perhaps explains the Rabbit’s suffering and that tear of despair from which the nursery magic fairy springs. Williams would likely have appreciated Misner’s words I quoted earlier: “Alison made me real. Alison ruined me. And I am better because of it.”

Margaret Blount quips, in Animal Land: The Creatures of Children’s Fiction, “The path of every toy is always downwards” because while we give them human attributes, breakable and disposable toys they remain. She asks, “When such creatures are given thoughts and emotions, how can they be other than tragic?” Blount answers her question with The Velveteen Rabbit:

The only way out of the difficulty is to turn toys into cheerful ageless beings such as Larry the Lamb or Winnie the Pooh, neither of whom lives in the real world at all, but in some place where a small boy and his bear will always be playing. But the fairy-tale satisfaction of this short, perfect allegory would not be valid if the rabbit were not part of the child’s real life. The allegory is about human love and human childhood.

While the magical ending isn’t realism, it’s realistic in its aims: to show the spiritual rewards of loving through a lot of misgivings and discouragement. Williams aimed to create what she called “imaginative literature as an interpretation,” something she admired in Dhan Gopal Mukerji’s writing about his mother, “the extraordinary gentle wisdom with which she used legend and stories to interpret the spiritual problems of life.”

Many early shapers of children’s literature in the United States found Williams to be not only a talented writer but also an insightful critic whose ideas influenced the direction of the field. Bertha Mahony Miller found her “a rarely able critic” and valued her advice on manuscripts submitted for publication in The Horn Book. Moore also lauded Williams’s “rare quality of criticism.”

After the author’s death in 1944, Moore and Miller collaborated to edit Writing and Criticism: A Book for Margery Bianco, in which they recount why they were “impressed with the quality and variety of Mrs. Bianco’s interests, her skill as a writer and translator, the reliability and richness of her background, and, above all, by the wisdom, the humor, the spiritual integrity she brought to the field of children’s books after World War I.” Intended “to make something of Margery Williams Bianco’s life and work known to later generations,” this book, ironically and unfortunately, is now rare and found primarily in special collections.

Despite the efforts of her contemporaries who themselves have become legends, most of Williams’s contributions to the field of children’s literature are in danger of being lost to history. Perhaps this has happened because, in the words of Eiss, “Her writing is a product of a time when children’s literature presented an ethos that many children and critics find unrealistic today, an ethos combining love, beauty, health, nature, God, family, truth, and the natural goodness of the child’s worldview.”

Perhaps a pandemic ethos during a time of global climate change and alternative facts, dovetailed with the hundredth anniversary of The Velveteen Rabbit, will ignite renewed interest in the author’s life and collective works.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Velveteen Rabbit at 100, edited by Lisa Rowe Fraustino. Copyright © 2023. Available from University Press of Mississippi.